Benedikt and Cline

A Virginia writer's detached study

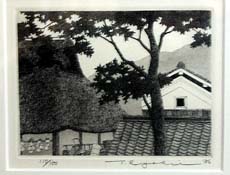

Isuien garden, Nara, Japan

Woodblock print by Tanaka Ryohei

Michael Benedikt appeals for an architecture that can "halt the slow slide of architecture (and just about everything else that is slow, physical, natural and real) into the world of television." (Benedikt 1988a, 6) Benedikt wants buildings that show forth their own and our "reality," assertive buildings, sure of themselves, with import in the life of a community, showing forth their stubborn materials in a way that goes beyond human willfulness and easy totalities. Places are different from buildings, but Benedikt would also look for places that were clear and authoritative in their melding of grammar and locale, places whose grammar and activity engage activities that matter to the community and connect with basic dimensions of our mortal life, places that emphasizie their physical presence, seeming in their design naturally fitted to their grammar without arbitrary or willful imposition, and not defining their inhabitants down into tight or abstract roles.

In a similar vein, Ann Cline worries about "What can defend ordinary reality in the face of 'virtuals' of all sorts?" (Cline 1998, 88)

The target these writers are aiming at differs somewhat from mine. We agree on the need to escape shallow inhabitation and superficial places. They worry about an architecture busy with Meaning and moving too fast instead of putting us in touch with the sheer presence of things and our own finite being. I worry about serial simplified intensities that level out the complexities of our situation. The worries are related, both legitimate, but not quite the same.

Benedikt calls for "direct esthetic experience of reality" where the world is perceived afresh, in a way that is free from desire yet opens us to joy and possibility, where things are significant without being symbolic, and where buildings are free from the demand to communicate. (Benedikt 1987, 2-8) Cline urges periodic withdrawal to "huts" for ritual and less busy encounter with things and our fellows. In the Buddhist terms that Benedikt alludes to, this is to encounter the suchness of an object and our situation with it. I agree, but protest that our situation's suchness includes complexity and linking.

Ultimately the issue here is ontological. I disagree with their tendency to equate reality with full presence. Reality also involves mediation, and so absence, connection and linkage beyond current presence. The concrete being of a place is in its links and negations and complexities reaching out to horizons beyond immediate view, as well as in its sheer presence and bodily influence. Not all the real is found in chopping wood and drawing water. Our tasks are more complex -- even the old Zen masters had to deal with bureaucracy and a complex social structure. We may need the isolation of the hut, as well as its zone for self-aware sociality in a marginal place of mutual discovery. But we need more.